Discover more from The Grizzly Bear Diaries

Western Canada is burning again.

For the third summer in seven I am waking up each morning and heading straight for the internet to check the latest reports from the British Columbia Wildfire Service.

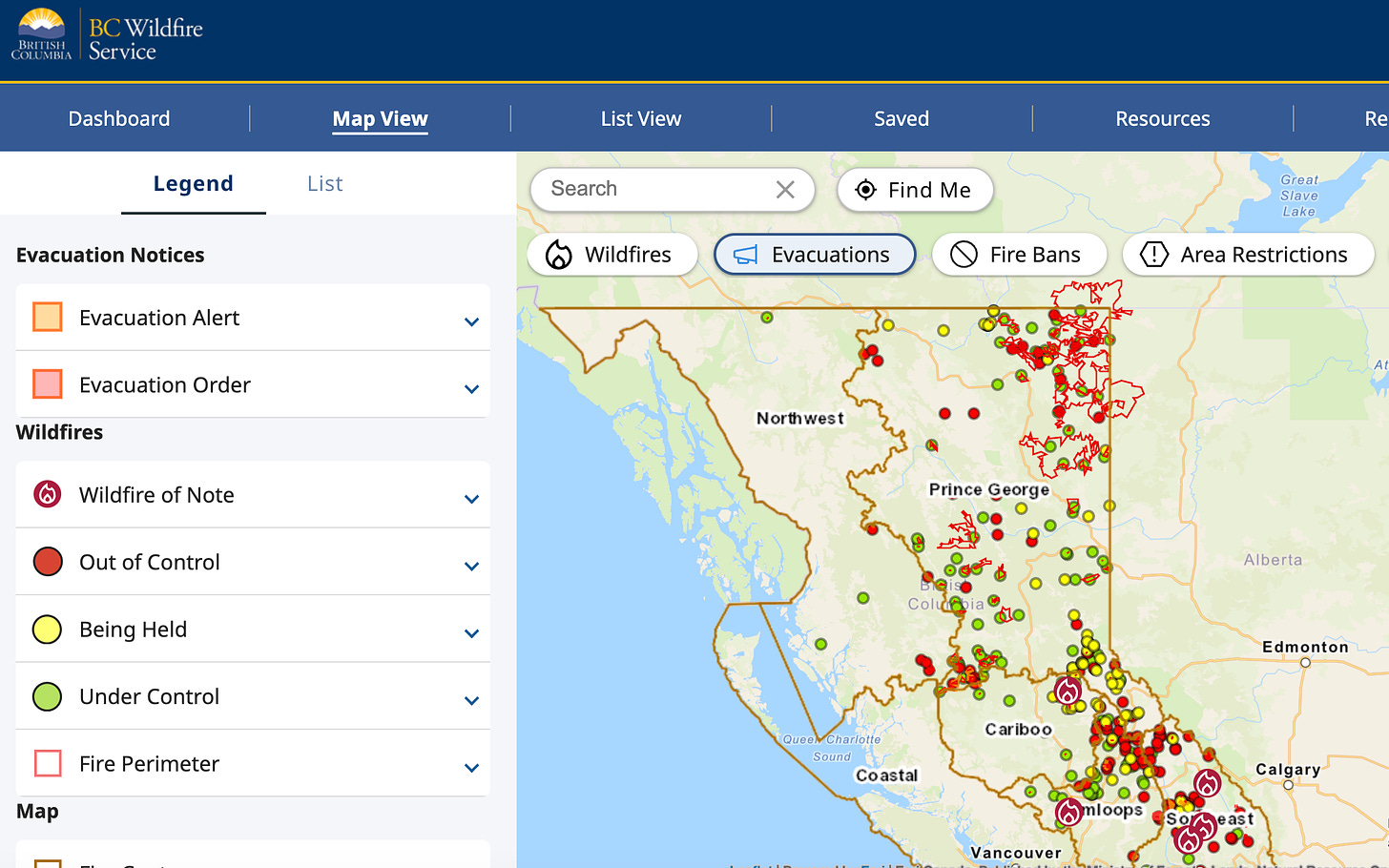

An updated map shows fires that are new, fires that are under control, and, by far the most numerous, fires that are out of control.

If you use the zoom feature the images becomes more granular. A thin red line appears which shows the perimeter of each fire (and some are huge).

A yellow-shaded block shows an area under evacuation alert and a red-shaded block areas where residents have been ordered out.

Many of my local friends now live in red-shaded areas.

When about a third of Jasper, one of the Rockies’ most storied and lovely towns, burned to the ground last week it made national and international news.

The flagship Canadian television news programme sent a reporter from out east to transmit live against a dark-grey sky and talk to devastated locals who had lost their homes and businesses.

The scientists have been saying for some times that the writing was on the wall.

In June 2021 a small BC town, Lytton, a few hours drive to the west, clocked 49.6 Celsius, the highest temperature ever recorded in Canada.

The next day a wildfire – possibly sparked by the wheels of a passing train – swept through town. Within hours the settlement of 250 was a pile of ashes.

So just why is western Canada so susceptible to wildfires. Why is almost every summer now dominated by smoky skies and burning hillsides?

The reasons are well-documented.

For one Canada and the north are warming at up to twice the speed of the rest of the planet. As a result the local ecology, unused to such rapid change, simply hasn’t had time to adapt.

In our valley – formed in the wake of the retreating ice age 10,000 years ago – the trees have had millennia of moderate rainfall in the spring, summer and autumn, and heavy snow in the winter. They simply aren’t designed for dry 40 degree temperatures.

And then there is the fact that before the 20th Century, when we began to industrially manage the landscape, small wildfires were common – sometimes even induced by the First Nations – and then left to burn to their natural limits.

As a result fuel build-up – especially old, dead and dried-out wood – was consumed before it could present an overwhelming hazard. The forests were thinner, there were more grasslands, and the forest floor cleaner and less littered with woody debris.

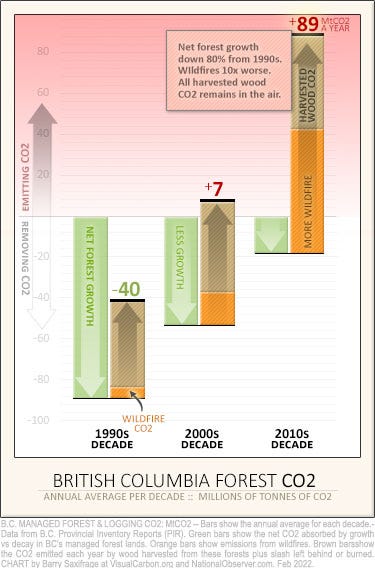

But perhaps the single biggest driver of forest fires is climate change. And BC’s biggest driver of climate change is the province’s logging industry.

Even as British Columbians have turned trees into a cash crop – chopping down millions of acres of forests – logging has pumped millions of tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere.

Until recently BC’s forests were one of the world’s most important banks of carbon storage. It’s trees – as they grew - sucked in carbon dioxide and pumped out oxygen.

But logging waste – huge piles of ‘slash’ that are left to rot on backroads throughout the province - now emits more carbon than the forests can take in. The forests have gone from being a mitigator to a net contributor to climate change.

And, if that weren’t bad enough, the emissions from the forest fires themselves have become another major accelerant of climate change.

According to some estimates they exceed all the man-made emissions in British Columbia combined in terms of the amount of carbon they pump into the atmosphere. BC, then, has become a menace, both to itself, and to the world.

What does all this mean at a local level? It’s not like residents don’t know what’s going on.

Argenta, the community down the road which was evacuated last week, was recently home to some of the biggest anti-logging protests in our area.

But despite a groundswell of opposition the local logging contractor won, the protestors lost, and a hillside outside town went for the chop.

It would be easy, of course, to blame the loggers themselves. But it would also be missing the point. Several of my local friends work, or have worked, as forestry contractors, road-builders and fallers. They are fine upstanding people.

In an area where good jobs are hard to come by, forestry promised an honest and relatively well-paid living out in the wilds. One of the most dangerous professions to be had anywhere, it harks back to Canada’s flinty pioneering spirit.

No vision of British Columbia’s past is complete without images of hard-bitten lumberjacks rolling logs into rivers and dancing around on them as they careen downstream.

Even so, in campfire conversations, many of the loggers themselves privately acknowledge that forestry has become greedy. Government policy has been corrupted by the enormous wealth of an industry that brings the province more than 10 billion dollars a year.

Worse still, while the locals contend with denuded hillsides, the lion’s share of the profits end in the hands of a few large corporations.

As I write these lines I am not – in the interest of full disclosure – sitting on a smoky deck on my stoop outside the lodge. Nor am I sharing in the peril and discomfort of many of my neighbours.

I am actually in an apartment in central Europe tending to another arm of my professional existence: my career as a university lecturer. Then next week, with my daughter Emma, I will travel to Kosovo for the first public showing of a documentary film we made.

After that I have a week or two reporting in Ukraine pencilled into the diary.

But, of course, that could all change. The last time a fire came ripping down our valley I was also on a writing assignment, that time in deepest Russia.

I got the first plane to Moscow, then flew to Geneva, then Vancouver, then the closest airport to the lodge that was still open. From there I called Thierry, a friend with a Cessna light aircraft, who is our local commercial pilot.

“I’m sitting in Cranbrook,” I said. “Can you pick me up and get me through the smoke?”

“I sink so, Julius, I sink so,” he said with his heavy French accent.

An hour later the buzz of a small plane approached through the fug. I jumped in and we fiddled our way back through the mountains. When we landed a friend picked me up and drove me the last two hours home.

The next morning, still jet-lagged, I marched around the garden with a clipboard, writing down tasks that needed to be done.

The firewood had to be moved from the deck, plastic chairs taken away from the windows (they burn like torches when a wildlife comes through), and propane cannisters placed away from the buildings.

And then, just as I had completed my list, the wind changed direction, and the approaching fire reversed course. I waited a few days and then headed back to finish my reporting job.

So this time I am going to wait just a little longer before I head for the airport. My ticket back to Canada is not until the end of August.

By then hopefully, as summer comes to an end, the fires will be burning out. And by late September, when the bears comes down to fish in the valley, they should be a distant memory.

But until then there are still a few perilous weeks to go. The weather forecast calls for sun and temperatures in the mid thirties. Like my neighbours I’m praying for rain. I’ll keep you posted.

Please ‘like’ this below if you liked this post, and offer comments, positive or negative. It helps me adjust my offerings to the interests of my readers, and especially those who have been so generous as to pay for a subscription.

NEWS & LINKS

+ Our October grizzly-viewing spots for this year are filling up but we still have a few openings left. Click here for more information.

+ We have also now opened booking for 2025. If you think you might be interested you can check out our website or drop me a line on julius@wildbearlodge.ca

Subscribe to The Grizzly Bear Diaries

The story of a British war correspondent who moved to the Canadian wilderness and set up a bear-viewing lodge. And what happened next. By Julius Strauss. Since 2006.

Just a brief fire update. The fires have now abated. Argenta, one of our largest local communities, was saved when firefighters threw up a protective ring around the community. The lodge's safety was never in question, though a friend and neighbour did install sprinklers on our roofs just in case. September has brought customary cooler weather and plenty of rain. Luckily dangerous fires are still rare here outside high summer (late June - end August) and, for those who have asked, they have never affected the bear-viewing seasons when we have guests.

So very sorry for the people having to evacuate and those who have already lost homes. It must be devastating and so hard to know how to start up again. Hope your lodge will be OK and the people there and that yu dont have to go back earlier than planned. All the best for your film showing and in Ukraine. Thank you for the interesting informative article. I had not realised that slash contributed to carbon emissions. There is a lot of slash which is just left in New Zealand and when there is bad weather it also contributes to loss of houses, and damages houses. But I hadnt known about the carbon effect.